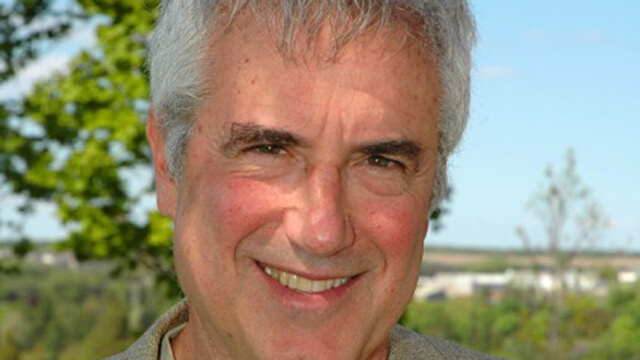

Golf writer Lorne Rubenstein’s illustrious career began in the caddie ranks

Reading a Lorne Rubenstein column or book draws a golfer closer to the soul of the game. Depth, passion and nuance have peppered his writing through 40 years of stories from courses around the globe, covering the professional tours, swing instruction, golf course architecture and his personal adventures.

In addition to authoring 14 books, Rubenstein wrote regularly for Canada’s national newspaper, The Globe & Mail, for more than three decades. Those archives are filled with words written about colorful characters, such as Alfred (Rabbit) Dyer, who caddied Gary Player to victory in the 1974 British Open or Hugh Stacy, longtime caddiemaster at Loxahatachee Golf Club.

Telling those tales came naturally to Rubenstein, considering the role caddying played in fueling his initial love for the game and the springboard it provided to a remarkable writing career. Rubenstein, 69, received the 2018 PGA Lifetime Achievement Award in Journalism. Time spent in the caddie yard and inside-the-ropes gave him a unique perspective and provided his readers with another layer of insight and experience.

RELATED: Scotland’s ‘Caddie School for Soldiers’ helps veterans find footing as civilians

An accomplished player himself — Rubenstein qualified for match play in the 1977 British Amateur — the time he spent walking alongside professionals in competition revealed they were vulnerable to the same mental demons which plagued other, less talented golfers.

“They were uptight about their golf swing and what was happening, good breaks, bad breaks. The things that were going on in my mind in tournaments as a low-handicap player were going on in their minds as well,” Rubenstein said. “So I had a lot of empathy for them, really. I knew how tough the game was at a reasonably high level of amateur golf and it was that much more difficult in professional golf.”

During his introduction to golf at age 12 or 13, Rubenstein caddied at York Downs, a private country club in the Toronto suburbs, earning $1.75 a loop, which allowed him to play golf there and also afford the 45 cents greens fee at the nearby muni, Don Valley.

His first foray into professional tour caddying occurred years later during the 1970 Canadian Open held at London Hunt & Country Club in London, Ontario. Rubenstein was attending college at the time.

In those days, prospective caddies put their name on a list and hoped they could land a bag for a pro who didn’t have a regular caddie traveling with him to each tournament. At first, Rubenstein was thrilled to be assigned Bob Murphy, the smooth-swinging U.S. Amateur and NCAA champion, who finished runner-up in the 1970 PGA Championship.

Murphy ended up bringing his own caddie, which sent Rubenstein scrambling to find a bag. He put to use skills that would serve him well when he began reporting on golf a decade later and landed the bag of Tour pro Bob Dickson.

“I just went over to the course where they were having the Monday qualifying and saw a big car, I think it was a Cadillac, with Oklahoma plates on it,” Rubenstein said. “He qualified. I picked up his bag and that’s where the caddying started.”

Rubenstein and Dickson became friends and teamed up three or four times each summer in the following years. Through the relationship, Rubenstein met other pros such as Dave Stockton and became comfortable around the Tour.

“I never really had illusions of being a professional golfer or aspirations to be anything but a good amateur golfer,” he said. “I enjoyed caddying, learning about the game.”

Rubenstein graduated from York University in 1970 and earned a masters degree four years later. During his British Amateur appearance he played a practice round with the young Canadian phenom Jim Nelford, which led to another caddying relationship that propelled him into writing full steam.

He was on Nelford’s bag for the 1980 Canadian Open and before the tournament approached Globe & Mail sports editor Cec Jennings about writing a daily column from a caddie’s point of view. Jennings agreed. Opening rounds of 68 and 70 put Nelford on the leaderboard. Though he faded on the weekend, the next step had been taken to move Rubenstein toward a career in writing.

Jennings told Rubenstein if he was out on Tour caddying again, the Globe & Mail would take more columns. Rubenstein, feeling emboldened by seeing his byline in the paper he’d grown up reading, proposed a more regular agreement.

“I said, I think golfers in general, keen golfers, are just interested in all aspects of the game. They’re interested in the pro tours, yes, but they’re also interested in architecture, equipment, the literature of the game, everything, I just suggested a column. The Globe & Mail was always a writers’ and readers’ newspaper like the New York Times of Canada.”

The partnership lasted 33 years. Rubenstein withdrew from a doctorate in psychology program and began weekly columns year-round and daily dispatches from major championships, Ryder Cups and the Canadian Open. His success on those pages led to an instructional book with eight-time Tour winner George Knudson, which led to other books and regular columns in magazines around the world. He was also the first editor of ScoreGolf Magazine.

“I had an enjoyable career writing golf when golf writing was in the ascension,” he said. “There were many publications and they encouraged longer pieces.”

In those early days, straddling the line between caddying and reporting posed the odd challenge.

“I enjoyed talking to the players about the game,” Rubenstein said. “I always had a notebook out there. One time Nelford looked at me, kind of laughing, but also at the same time serious. ‘OK, are you caddying here or are you taking notes for an article?’ Everything was material, I saw what a razor’s edge there was out there between succeeding and missing the cut.”

Rubenstein has enjoyed watching the evolution of professional tour caddies. In his moonlighting stints, he understood the tough road ahead for those chasing the Tour. Only caddies for superstars like Tom Watson, Johnny Miller or Jack Nicklaus could make a decent living at that time.

“It’s an evolution in the way caddies are treated, the food you would eat and the places you would hang out,” he said. “In those early days sometimes it was a caddie pen and not much else was provided for the caddies. That got way better even over the years I was doing it.”

From the inside story of Tiger Woods’ historic 1997 Masters victory, to a season in Dornoch, honest stories about Moe Norman and countless reports from locker rooms and putting greens, the golf world is better for Rubenstein’s writing and it’s writing enriched by days spent with golf bag on shoulder, notebook in pocket and grass underfoot.