The life-changing loops of Bill Leahey

Bill Leahey knows becoming a good professional caddie is all about being in the right spot.

And we’re not just talking about where he stands on the golf course.

If we had a GPS on where life was going to take us when we were young, that would help. But wouldn’t that be boring?

Leahey never imagined a life where he would caddie on the PGA Tour in five decades — that doesn’t happen often — even though this seldom was his full-time job.

Some of his career choices were by design, most by fate. Such is life.

But when you grow up close friends with someone who would become a legendary caddie, there’s a good chance that looping will become part of your life, too.

READ: Here’s the story of a caddie best known as ‘Shakes’ and his dream of landing a PGA Tour bag

Leahey was good friends with Bruce Edwards for as long as he can remember. They played Little League together growing up in Wethersfield, Connecticut, a small middle-class town just south of Hartford.

They caddied together at Wethersfield Country Club, where Edwards’ family was members. And when it came time to make a living, they took their ride-or-die friendship to the PGA Tour, which at the time didn’t exactly open their arms to caddies.

Leahey even got to caddie for Hall of Famer Tom Watson several times in his career, including as recently as 2012. Leahey, however, wasn’t celebrating that partnership.

“It was for the wrong reason,” Leahey said.

It was because his childhood friend, Edwards, had died of ALS in 2004 at 49.

*******************

Bill Leahey grew up 2 miles from the Wethersfield Country Club, which hosted the Insurance City Open, the forerunner to the Travelers Championship. It was inevitable he would become interested in golf.

Leahey started caddying at Wethersfield CC when he was 14. He got $4 a round per bag and a $1 tip if he did a good job. There were days when he would go home with $20 in his pockets.

“I thought I was raking it in,” Leahey said. “I fell in love with caddying.”

In addition to the money, caddying at the club also gave him an opportunity to carry a bag for a professional in the Insurance City Open, which was a huge deal for a teenager. Leahey’s first chance came in 1967 when he looped for a local pro named Frank Segaline.

The highlight came during Wednesday’s practice round. One of the players in the group was a young pro who had a distinct swing and swagger.

“It was Lee Trevino,” Leahey said. “He shot 65 that day. I never saw anyone shoot a 65 and he had that great personality. The next year he won the U.S. Open. That was a pretty good start to caddying.”

Soon, Edwards joined Leahey as a caddie at Wethersfield, bringing his long hair and free spirit with him. They worked there together throughout high school. After his sophomore year at Upsala College, Edwards persuaded Leahey to spend his summer of ’73 caddying on the PGA Tour.

Edwards originally wanted to get a job at Disney World, so he drove to Orlando for an interview. It was a short one.

“They said he had to cut his hair to work at Disney, and Bruce didn’t want to,” Leahey said. “Bruce stopped at the PGA Tour event in Greensboro on the way back and called me. He said ‘Nobody is here. It’s easy to get a bag.’”

On July 3, 1973, Leahey and a friend, Dennis Turning, got on a plane and headed to Milwaukee to catch up with Edwards on the PGA Tour.

This was when there were few full-time caddies on the PGA Tour, most of them black. Arnold Palmer had Creamy Carolan and Jack Nicklaus used Angelo Argea, one of the few white full-time caddies. Only 60 players were fully exempt, so it was difficult for caddies to make a consistent living unless they worked for the top players.

Caddies weren’t exactly high on professional golf’s totem pole, either. They were not allowed in the clubhouse or the pro shop. They had to stand in the parking lot and hope and pray they could find a player who needed a caddie.

“We were kind of looked at as dregs of society,” Leahey said. “A bunch of nobodies.”

During their second week on tour, at the Robinson Shriners’ Classic in Illinois, Leahey got his first big break. He recognized Lou Graham, a member of the Select 60, walking in the parking lot with his clubs slung over his shoulder.

Leahey knew he had nothing to lose.

“I said, ‘Mr. Graham, I’m Bill Leahey and I’m out here caddying. Can I caddie for you this week?’” Leahey said.

To Leahey’s amazement, Graham said yes and handed him the bag. “Second week out and I luck into that,” Leahey said.

They cut a deal where Leahey received $150 a week, plus 3 percent of Graham’s earnings. (Deane Beman made $25,000 for winning that week, so most of the caddies weren’t exactly raking it in.) To cut costs, caddies often stayed with families or four (or six) of them would pile into a hotel room and split the bill.

Leahey would have slept on a bed of nails if need be. Halfway through college, and already he had a job he loved and a great boss.

“Lou was a wonderful guy,” Leahey said. “A true Southern gentleman. He took great care of me.”

The following week, at a tournament in St. Louis, Edwards got even luckier when he met Watson and was hired on the spot. The two Wethersfield kids were doing quite well.

Next up was the PGA Tour event at Westchester, which featured the largest purse on tour; the winner received $50,000 – more than even the majors. This was the first year Tour caddies were allowed to work at Westchester.

Leahey was so worried he might show up late for Monday’s practice round he arrived at the course the night before. He had no idea where to go – it’s not like he could use a cellphone to get information.

Leahey was prepared to sleep outside on the grass until a security guard spotted him and was kind enough to take him inside where he slept on a leather sofa adjacent to the locker room.

The next morning, Leahey awoke in a panic: He knew he was somewhere he wasn’t supposed to be and was afraid he would get tossed out of Westchester if he was spotted.

“Here I am with long hair, wearing a T-shirt of a recent tournament and I walk around the corner and there are 30-to-40 guys, all New York City cops,” Leahey said. “I thought they were going to knock me out. Somehow, I got out of there and high-tailed it to the 10th green to wait for my caddie buddies.”

When summer ended, Leahey returned to college and handed off Graham’s bag to Turning. As much as he loved caddying, Leahey was determined to get a degree.

When summer returned, Leahey returned to the PGA Tour, caddying for Steve Melnyk in 1974 and Allen Miller in 1975. Leahey graduated from Upsala in ’75 with a double major in political science and philosophy, the latter seeming a perfect choice for a caddie.

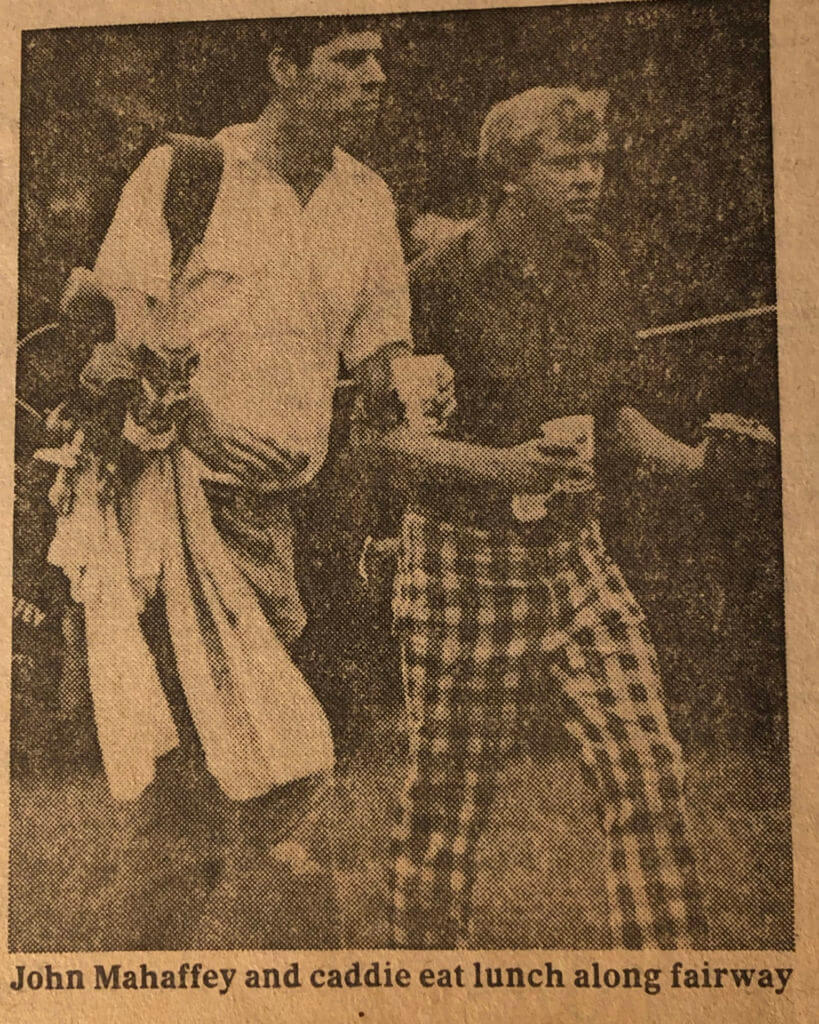

Leahey decided he wanted to take a year off before getting a “regular” job, not wanting to give up his independence even though he had a girlfriend. He caddied for John Mahaffey, who would win 10 PGA Tour titles.

“John was one of the best ball strikers, almost winning two U.S. Opens in a row,” Leahey said. “If there was one thing that kept him back it was he wasn’t one of the great putters.”

Mahaffey said the only reason Leahey was caddying for him was Edwards had been his caddie and he grew tired of his on-course outbursts.

“I went through almost every caddie out there,” Mahaffey said. “I was the hardest guy in the world to work for, which is something I’m not proud of.

“Bill was probably the best caddie I ever had. He was always attentive to things, always on time. He always had a smile and was upbeat. He had all the pluses and none of the minuses.”

When Leahey felt it was time to give up caddying for a corporate career, he switched roles and asked Mahaffey for advice.

“Bill came to me and said I have a chance to take this real good job,” Mahaffey said. “He said that he really enjoyed working for me, but he wanted a family. I told him if you don’t take that job, you’re crazy. You’re a smart young man. You’ve seen the road and now it’s time to settle down.”

Leahey moved back outside the yellow ropes and got married and had two children. He took the corporate job, moved to New Jersey and didn’t caddie again until he got a call from his buddy Edwards in 1980.

“Bruce said his girlfriend’s father had just committed suicide and he needed me to come to Congressional to caddie for Tom (Watson) at the Kemper so he could be with her,” Leahey said.

Leahey’s world changed that week, but not how you would have imagined. While caddying for Watson in the pro-am, one of the amateurs in the group took an interest in Leahey. At the end of the round, he handed Leahey a card and told him to call him.

“The guy, Jeffrey Kahn, worked for Smith Barney and he offered me a job at a new office they had opened in New Jersey,” Leahey said. “It turns out it was 1/8th a mile from the house we had just moved into.”

That was even better news than when Watson finished runner-up to Craig Stadler that week, earning Leahey $2,500. Leahey would work at Smith Barney for 26 years.

Getting to work for a young star player such as Watson was a great experience for Leahey, who would caddie for Mahaffey in the next two U.S. Opens. And not just because of Watson’s skills.

“Caddying for Tom was pretty easy,” Leahey said. “The only thing you have to pay attention to is to make sure you’re fast. He walks quickly, he’s decisive, and he wants you to be on the ball before he’s there.

“Other than that, he was an easy guy to caddie for. Another thing is it never was your fault; it’s always his fault. If he got a bad lie, he would say, ‘Well, I hit it here.’”

Leahey caddied for Mahaffey in two more U.S. Opens (1980-81), but his days as a PGA Tour caddie were over after 50-plus events.

In 2003, Leahey called Edwards, a huge fan of Philadelphia’s sports teams, to rib him about the Eagles. A woman named Marsha answered the phone.

“I knew Bruce was dating someone,” Leahey said. “She said Bruce wants me to tell you something.”

Long pause.

“He has ALS,” Marsha said.

What?????

“You could have knocked me over with a feather,” Leahey said. “It was one of the worst jolts I have ever had in my life along with watching Jack Ruby shoot Lee Harvey Oswald and 9/11.

“Bruce smoked cigarettes, but he was in great shape, healthy, active. For this to happen to him … nobody knows why you get it … it was brutal. We were literally best friends. This (disease) stole him from me and all of his friends.”

Leahey said when he told his longtime secretary about Edwards’ diagnosis, she confided she knew something was wrong with her boss’ close friend.

“She thought he was drinking, because his voice had changed … it was slurring,” Leahey said. “I had completely missed it.”

Edwards continued to work for Watson in 2003, but Leahey stepped in again for his friend at the PGA Championship because it was held at Oak Hill, a daunting walk for a healthy caddie. (Leahey also caddied for Watson in several tournaments in ’04, winning the Wendy’s Champions Skins Game, while another of their caddie buddies, Neil Oxman, took over when Watson played the British Open.)

Leahey spent the rest of 2003 visiting his old best friend as often as he could. Leahey said it was more difficult for him to see Edwards.

“Bruce was amazing,” Leahey said. “He never bitched about it, he never cried on my shoulder. He never said he got screwed. All he said was, ‘I made a quad,’” referring to the dreaded score.

Edwards was named the winner of the 2004 Ben Hogan Award for courage by the Golf Writers Association of America. The award would be given to him in Augusta, Georgia, at the GWAA’s annual dinner the night before the Masters.

MORE DOLCH: There’s a whole lot more to caddie Lance Ten Broeck than his nickname ‘Last Call’

Edwards had planned on attending, but Marsha (now his wife) called the weekend before and said Bruce was too ill to leave his Ponte Vedra Beach home. Leahey had already planned on attending the dinner with several of Bruce’s caddie buddies.

“We called him on the way to the dinner and had a good talk,” Leahey said. “He told us to call him back afterward. Andy North came over and we talked to Bruce until after midnight.

“The next morning at 6:30, we got a call from Marsha telling us Bruce had passed. We went out and walked nine holes with Tom.”

After the shock, came the resolve. Edwards’ many friends, led by Watson and author John Feinstein, who had written a biography (“Caddie for Life: The Bruce Edwards Story”) that came out just before his death, decided to start a foundation in their friend’s name to find a cure for ALS.

Every summer they hold a charity golf tournament where Watson, longtime caddies and entertainment and sports personalities come together to raise money and remember their dear friend. They have raised more than $5.5 million and Leahey hasn’t missed one yet.

“It’s a great way for me to stay in touch with these people,” Leahey said, “and it still feels like Bruce is around when we are there.”

Leahey’s last job as a caddie was for Watson at Greenbrier in 2012, but at 66 he remains interested in his old profession. Leahey, who lives in Southport, North Carolina, knows how hard the job was and he’s proud of what it has become.

“It was fun to be inside the ropes,” Leahey said. “Once you’re there, you never want to be outside of them again. It wasn’t an easy job, but we had a lot of fun in our little universe.

“I am very proud of what the role of the caddie on tour has become, both in terms of professionalism and general respect. They make a great commitment, adapt to change, face the grind of travel and perform under the gun. They are great ambassadors for the game.”

Leahey mentions caddies such as Mike “Fluff” Cowan, Mike Hicks, Tony Navarro, Billy Foster and Mark “Fooch” Fulcher as among the caddies he admires most. He respects them all.

Leahey knows he won’t be remembered among those caddies because he didn’t do it long enough, and he’s fine with that. He has the memories and the opportunity to walk the same path as his childhood friend for a few years.

“I met a lot of guys I’m still close friends with today,” Leahey said. “I never got fired. I always did a good job. I was always on time and I was diligent. I’m proud of that.”

So would be Bruce Edwards.

Nice that you caught up with Billy, a class guy and longtime great friend. Enjoyed all the pictures including Drew and myself. Keep up the good work!

Gary,

You probably don’t remember me, Michael Shea, we were classmates at Wethersfield High School. Also remember caddying at Wethersfield CC, especially for all the rookies in my case.

Mike

What was your nickname. I remember riding around in your mustang